Confessions of a Scum Scholar

“But the beauty is not the madness

Tho’ my errors and wrecks lie about me.

And I am not a demigod,

I cannot make it cohere.

If love be not in the house there is nothing.”

Ezra Pound, Canto CXVI

“The trick … is not minding it hurts.”

It’s taken me a year to write this essay. It’s going to be a huge mess because my thoughts are a huge mess. I think that is probably the only way to write this memoir. I have agonized over the perfect expression; the perfect cohesion of my ideas; and it will not come. I am trying to understand myself.

This morning I watched Nobuhiko Obayashi’s final film Labyrinth of Cinema (2019). It is a wonderful, huge, messy thing. Obayashi, who is mostly only known to western audiences for his horror/comedy House (1977) made over 30 movies across a 60-year career; when he made Labyrinth, he had had lung cancer for three years following a prognosis of only a few months. It feels like a movie by someone who has spent his whole life in love with movies, putting everything up on the screen left to say, the apotheosis of every thematic and stylistic impulse his art has striven for over a lifetime. Four characters are swept into a movie theater in Obayashi’s hometown on its final night open due to a cataclysmic storm, and before long are literally pulled into the movies themselves. One other visitor, Fanta G, (portrayed by Yukihiro Takahashi, lead vocalist for Yellow Magic Orchestra, who himself passed away in 2023), arrives in a spaceship of sorts, declares movies are “a cutting-edge time machine,” and functions like Obayashi-as-commentator while the film unfolds. Through a series of war movies, the characters are pulled through the history of Japan since the end of the Tokugawa era, and it routinely blurs the lines between fact and fiction, juxtaposing movies against the true historical events they depict. Characters slide across time periods, and quickly stop being the people they were before entering the movies and transform into some amalgamation of factual historical person, on-screen depiction, and their real, embodied selves. Also, one of them may be the ghost of a girl who was killed in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and she might also be the elderly woman running the ticket counter. “There is truth in a lie,” the characters constantly remark; Noriko, the ghost girl, claims she goes to the movies to learn, because she knows nothing. Obayashi made Labyrinth of Cinema on the tail end of a trilogy of anti-war movies – Casting Blossoms to the Sky (2012), Seven Weeks (2014), and what he thought would be his final film, Hanagatami (2017) – with Labyrinth serving as a coda to that trilogy, a final thesis statement that argues (speaking directly to the audience) that while we can’t change the past, movies might change the future, and that young people should study movies in order to build a better world.

I’m pretty sure I’m going through some kind of mid-life crisis. I turned 38 this year, so it sort of makes sense. My dad died in 2018 when he was only 57. His death feels unresolved in my brain. It was a surprise, but also not a surprise. Not entirely on purpose, but not entirely an accident either. It was a moment of grief, but I struggled to grieve and felt conflicted by feelings of relief. He had struggled for decades with alcoholism and depression, and things really started to fall apart for him at about the same age I am today. I have very distinct memories of living with and around him when he was my age; I was finding my passions in literature, movies, and games, discovering the internet and joining communities, all formative experiences that still have their tendrils in me (at this very moment, in a second window, I’m in a Discord group of people who I met on a Final Fantasy message board at that time in my life, talking to the same people I met way back then.) But more difficult for me imagining where he was is where he went. 57, when he died, is only twenty years away from now (19!). Twenty years feels like nothing. Ten years ago I lived in the same city I do now, in a house only a handful of blocks away, associating with a lot of the same people as now, working for the same institution I do today. The time between ten and twenty years back feels even more compressed; I was leaving high school, embarking on college, feeling like the future felt impossibly open, and before I know it ten years have passed and I’m getting fired from a job I hate and thrown back into academics. Twenty years ago I was ready for a career as a fiction writer; ten years ago I was firing on all cylinders to become a scholar. So far as I can tell at 38, I’ve failed at both things. I occupy a strange space somewhere between, marked (in Calibri font?) mediocre; not quite a working writer, not quite a true scholar. I teach college students how to write and how to interpret literature, but do neither thing professionally. As the worst maxim ever goes: those who can, do, and those who can’t, teach. A scum scholar, if you will.

“Why deny the obvious necessity for memory?”

Labyrinth of Cinema made me think a lot about a long-time favorite of mine, Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) from Alain Resnais. The atomic bombing of Hiroshima serves as a fulcrum point for both; Labyrinth “ends” its history lesson there; Mon Amour begins at it. Two lovers meet in Hiroshima, a decade and change after the end of the war; the French woman (called Her) is there to appear in an anti-war movie about the bombing; the Japanese man (called Him) lost his family to the atomic bomb, and now works as an architect rebuilding the city. The first lines of the film announce this tension: “You saw nothing in Hiroshima. Nothing,” the man says to Her. “I saw everything, everything,” she says back to Him. Mon Amour performs a similar feat of legerdemain as Labyrinth; it moves freely between authentic newsreel footage, the re-enactment of atrocities for the film the French woman is making, her own past experiences, as well as the present moment the film takes place in. Past and present are compressed into one, both characters enduring their own traumas of the war and the struggle to move forward. It’s not really a movie about a love affair or about Hiroshima, but rather a movie about the weight of time and memory, of unresolved pains, and the dissatisfaction in seeking or finding closure. Labyrinth of Cinema says we can move forward, but Hiroshima Mon Amour casts doubt on this. Cognitive dissonance is defined as attempting to hold two competing and contradictory ideas in your mind at the same time.

You know what movie I also really love? Gojira (1954). It’s a about a man who believes he has become a monster for creating a bomb that destroys a monster created by the bomb. The Americanized Godzilla was considered genre pablum, “creature feature” schlock even when it was released. But Gojira possessed an intellect and pathos noticeably absent from its decades of sequels, causing it to elevate in esteem over time while its legacy denigrated to high camp for children. To be honest, I think I love those even more – my favorite is probably Godzilla Mothra King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001), which has the best title of any movie ever and I watched for the first time the same week I was fired from the job that led to getting a Masters degree in English. The franchise has rebooted at least four times, with each reboot treating the 1954 film as gospel and de-canonizing the other sequels. Past and present compressed, incapable of moving on from a metaphor about the atomic bombing in 1945 produced in 1954.

For as long as I can remember I’ve never entirely felt like I belonged where I was. When I was kid, there was always this feeling that I was part of a fallen family. My understanding was that my father’s upbringing was quite privileged. His father was a radiologist; they lived in the wealthiest neighborhood in the small western Nebraskan town I was born in; they could afford to send their eldest son to a private academy, and they did things like take regular skiing trips (my father was apparently so enamored with skiing that he made it his entire personality for many years, opting to live and work at a resort instead of attending college courses). They were socialites, country club members, known quantities in the community. That all came crashing down when my grandfather killed himself, a few years ahead of my birth; I later learned that he had been hiding huge sums of money in tax shelters, and eventually got caught (a memory: shadowing a reporter at the local newspaper for career exploration in high school, looking up the instances of my family name in their archives, and learning exactly how much money he hid and exactly how much trouble with the IRS he got into). My father ended up a college dropout, working in an auto dealership my entire childhood. My mother worked as a waitress, gave birth to me at 19, and after their divorce supported my younger brother and myself with Burger King wages. We lived only a handful of blocks away from my widowed grandmother, a real-life Miss Havisham who could never really let go of her past. She died the week I enrolled in graduate school, and I read my assigned Ezra Pound on the way to her funeral. “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley,” I recall. All things are a-flowing, Sage Heraclitus says/ but a tawdry cheapness shall outlast all days.

It was about this time that some feelings about art and the merit of art had started to crystallize for me. I was reading Ezra Pound alongside the other American modernist poets; William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, Marianne Moore, and the like. They were all distraught by the state of art and poetry at the turn of the 20th century and had perceived a terrible ossification in artistic expression: art had simultaneously become buried in layers of pretentiousness and distance from their audiences while also drowning in a sea of shallow garbage, mass produced for everyone and nobody. It was easy to feel attracted to the world and ideals of the “lost generation,” because it felt like I was part of a newly lost one myself. I was in graduate school because I was fired from a finance job I was miserable in, and not terribly long after enrolling I was marching in Occupy Wall Street demonstrations. I was spending my free time bumming around coffee shops and bars, fraternizing with my similarly dispossessed peers – burnouts, struggling artists, libertines, the works. It was the poorest I had ever been in my life, momentarily jobless and existing purely off the subsidy of student loans. It was wonderful. Beyond the modernists I would eventually cut my teeth on theory: Edward Said, Jacques Lacan, Judith Butler, Frederic Jameson, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Julia Kristeva, on and on, filling up a quiver of theories and ways of looking at art, intoxicating me on the possibilities. (My generation has been frequently labeled overeducated and undervalued and I feel extremely attacked every time the notion comes up.) I could find few reasons to dismiss or write off a work of art, because there were so many ways to wring value out of it.

(Style choice: I want to try and avoid invoking theory in these essays. I’m reminded of a quote from Stephen Hawking in A Brief History of Time alleging there’s an inverse relationship between the number of equations you put in a book and the number of copies it can sell. I would like to keep this in mind.)

“I am what I am. You couldn't teach me integrity.”

I need to talk about Andrei Rublev (1966) for a moment. I will probably find a way to talk about a Tarkovsky movie every time I write one of these, so please bear with me, and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it for the last 8 months. Ostensibly, the film is a biopic about the titular 12th century Russian icon painter. It’s told in several vignettes, and none of them show him actually painting anything. The first episode has nothing at all to do with him: it instead depicts a medieval peasant building a contraption from balloons so he can fly. Everyone tells him to stop, that he’s mad for attempting this, it will clearly kill him, but we instead watch his success, seeing the world from above, his impossible glee from flight before crash landing. The second episode has Rublev and his compatriots entering an establishment where peasants are singing bawdy songs. Rublev’s inner turmoil concerns his need to express powerful, complex intellectual ideas that can be understood by the illiterate, the unobservant, the people who are simply trying to survive in an ugly, brutal world. There is a lot of violence and trauma in the film; Rublev at one point survives the burning of a church by invaders where hundreds perish. His fellow artists are blinded or murdered, and one episode is dedicated to his long dark night of the soul, burdened by failure and death all around him and entering a vow of silence. The penultimate episode also doesn’t feature Rublev, but instead is about the construction of a bell, coordinated by a literal child, figuring it out as he goes along because he is the last living son of a bellmaker who failed to pass the trade on to him. The episode ends in triumph, and gives way to the final episode where we finally see Rublev’s icons in the present-day, in full color and full silence, lingering over the subjects without explanation or narration, giving viewers the opportunity to marvel at his life’s work without the filmmaker’s guiding hand. It is a shockingly profound viewing experience. I think everything about art and being an artist is somewhere in Andrei Rublev: the need to express, the constant sense of doubt and impostor syndrome, a war between the sacred and profane, between egoism and ideal, the temptation to do literally anything else, the urge to bear witness to the pain and beauty of the world, the feeling that your work is really just a way to cheat death and offer hope that something you do will outlive you.

What the hell was I even thinking? That I could become a successful novelist or important scholar? I’m the son of a blue-collar worker and a teenage mother who borrowed every single dollar toward getting two English degrees. You dumbass. I didn’t get into this stuff because I had some preternatural talent for language or words, or because I was a K-12 wunderkind – I did it because I really liked video games, anime, and trashy kung fu movies. I had a 2.7 high school GPA. I barely passed Algebra, twice. I spent most of high school deeply resentful of my situation. My mother had remarried – her new husband was self-made, retired in his early 30s, swimming in money. They decided to build a house on an acreage out in the country. I was yanked out of a school I enjoyed in the city, where I had friends and connections and people interested in helping me carve out a future for myself. This new place felt alien, small, and insular. Everybody had already made all their friends, and the curriculum was a year behind, so I was stuck between two graduating classes. I didn’t belong and couldn’t belong, so I fell into the comfort of Final Fantasy and people I knew on the internet who also liked Final Fantasy. An enormous chunk of my identity at 38 can be traced back to having no friends, a PlayStation, and satellite television when I was 15. And even though my new stepfather had money, I never saw any of it. I was basically a guest in my own home, not so much his ward as I was his obligation, a burden one takes on merely as consequence to marrying the mother, all realities that came into focus years later when he divorced himself away from having anything to do with me, my mother, my brother, never to be heard from again. (There’s another Great Expectations allusion in here somewhere, I’m sure of it.) The only things I ever got from him were a slew of co-signed private bank loans for college, because he made too much for me to qualify for federally-guaranteed aid, and I decided to get an English degree because my comforts were video games, books and movies and I just wanted to spend more time with them. But there is truth within a lie.

Maybe this should have been two separate essays.

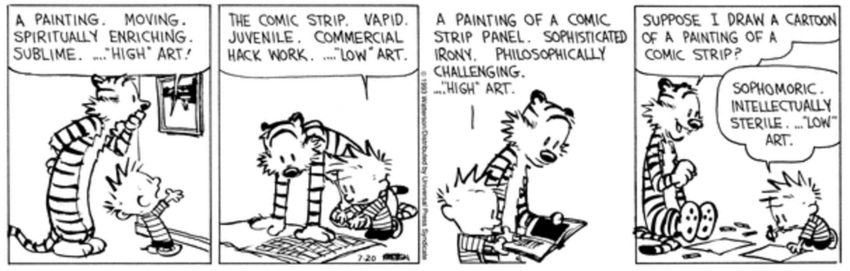

I don’t think we fully appreciate how easily a work of art can lodge itself deep into your brain and fuck you up forever. There is a Calvin and Hobbes comic strip that I probably first saw when I was 9 or 10 years old about the distinction between “high art” and “low art.” “A painting. Moving…spiritually enriching…sublime …’High’ Art!” Calvin declares. In the next panel: “The comic strip. Vapid. Juvenile. Commercial hack work. ‘Low’ Art.” The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book was probably my first exposure to an author’s inner thoughts about their own work, because it comes with a length prologue of Watterson’s grievances about being an artist and working within a medium that patently did not value the artistic merit of comic strips, weighing his influences and ambitions against the shallow and stifling expectations of the newspaper industry. The “high art/low art” strip distills that tension very elegantly – so much so that it has popped back into my head once a week for the last three decades of my existence. I waged a similar battle of my own as a student. I got a C+ in a Writing of Fiction class my Freshman year at the University, a class I had poured my heart and soul into. I got it because I was bad at following directions: I wanted to write fantasy stories against the wishes of my Professor, who was steeped in the late American realists, who had us read Tobias Wolff and Raymond Carver, and expected us also to write realist stories. “You can pursue a career writing fantasy stories if you want!” he said to me once. “You’ll make a lot of money doing it, but it won’t be art.” I produced essays for later classes grinding that ax; how different, really, are A Wizard of Earthsea and The Tempest? Even in Grad School, where I was obliged to produce work on TS Eliot and Mansfield Park in some classes, I was opting to take The Big Lebowski and Scott Pilgrim to task in others, like I was making some point to myself. I hated feeling like there was some arbitrary distinction dividing any of it. At the same time as I was developing all of these tools for drawing meaning and appreciation out of anything and everything, things like Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic were starting to become tastemakers, deciding for tons of people what to like, as if you could put a number next to a movie and that number decided its quality. I also read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance for the first time, a book about someone who literally goes insane trying to define “quality.” I became extremely fond of Armond White’s “low art contrarianism” as many labeled it, and user SuperMechaGodzilla’s verbose apologetics for trash cinema on the Something Awful forums, in large part because they were willing to buck trends and resist consensus-thinking, and they did it with wit and intelligence. I think it was also about this time that the Slavoj Zizek documentary The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology had released, throwing even more fuel on the fire. All said, I became extremely skeptical toward what could be called “formal” interpretations of media.

Let me tell you what I mean. I’m thinking about Ridley Scott’s Prometheus (2012) in particular. I can’t claim credit for this interpretation (you can find a summation of the original discussion here: http://prequelsredeemed.blogspot.com/2017/04/prometheus-questions-will-be-answered.html ), but discovering it changed the way I think about everything – it got lodged deep in my brain and fucked me up forever. Here goes. It’s not a particularly well-liked or highly esteemed film, either as a science fiction movie, as a sequel/prequel to Alien (1979), or as a product from auteur Ridley Scott. Audiences complained that the characters behaved irrationally, MacGuffins were not sufficiently explained, character motivations were confusing and unclear, all things that felt disappointing when contrasted against Alien, Scott’s initial foray that launched the franchise. Alien’s characters operate by the logic of realism, they are generally competent, etc. But the main thing to understand is that Prometheus really needs to be understood in context. Namely, Prometheus doesn’t want you to think about Alien, but 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) instead. Movies are a kind of cutting-edge time machine. Recap: 2001 is the story of humanity, where our evolution is instigated by some alien intelligence, then we are propelled forward to discovering the evidence of this hand, telling us where to go next; we send our best and greatest to pursue the signal, and one man is warped across time and space, pulled into the womb of our creators, and returned back to Earth an newly evolved, even greater species. Prometheus¸ on the other hand, is the story of humanity, where our evolution is instigated by some alien intelligence, an Elon Musk-analogue bankrolls a ship full of “ancient aliens,” Chariots of the Gods zealots and bad scientists propelled toward the signal, and when they get there, it turns out our creators hate us, and everyone dies in comedically ironic ways. The Elon Musk stand-in (impossible to unsee a decade after release, after Musk has unmasked himself as a largely incompetent manchild) begs his creator for eternal life and immediately gets bludgeoned to death instead. The biologist tries to make friends with an obviously hostile space rattlesnake and ends up with it down his throat seconds later. The person in charge of mapping the alien structure gets lost and perishes. No answers are given – at this point I should point out that the promotional campaign for the movie suggested to audiences that mysteries from Alien would be explained in Prometheus, and the back of the blu-ray packaging even has “questions will be answered” emblazoned across the top. “I go to the movies to learn because I know nothing,” like Noriko in Labyrinth of Cinema says.

(Top: 2001; Bottom: Prometheus)

What if a movie can be completely indifferent to its audience’s expectations? Aside from the mirrored plot structure, the fingerprints of 2001 are all over Prometheus. It begins with a direct allusion to the first shot in 2001. The evil robot in Prometheus is named David. When we’re introduced to David, he’s watching Lawrence of Arabia (1961) (shot on 70mm, exhibited as a roadshow, just like 2001), specifically the scene where Lawrence performs his magic trick pressing out a match with his fingers – “the trick, William Potter, is not minding it hurts,” which Lawrence calls back to only a handful of scenes later, Lawrence instead blowing out the match (cut to a sunset in the desert) in perhaps the most famous match-cut in cinema history, second only to the one in 2001, when a tossed bone transmogrifies into a space station. Movies are a kind of cutting-edge time machine. And of course Prometheus is enmeshed in the history of science fiction and cinema. Frankenstein is subtitled “The Modern Prometheus.” Scott quotes his own Blade Runner when introducing his Elon Musk caricature. There are little nods to The Fly (1985), Forbidden Planet (1956) (oh hey, wasn’t there a mention of The Tempest earlier?) and Quest for Fire (1981) sprinkled about it. When you throw in that Scott’s genre reference point when directing Alien was 2001, and specifically not the genre-schlock writer Dan O’Bannon envisioned, ex, The Thing From Another World (1951), Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), or Planet of the Vampires (1965), it seems impossible to read Prometheus as anything but a cynical, anti-2001, where people behave erratically on purpose, and pursue mundane ambitions on purpose, and the expedition fails to yield any meaningful closure on purpose. The trick is not minding it hurts. From this vantage point, Prometheus isn’t a failure or a disappointment at all. It almost seems like the audience’s perception of a failure is verisimilitudinous of the film itself.

“There is nothing in the desert and no man needs nothing.”

The trick is not minding it hurts. Sometimes an idea can get lodged in your brain and fuck you up forever. When I see what my peers have accomplished and have in their lives, it makes me feel like dying at 57 is too long to wait. How did I mess my life up so much? What did they do differently to be able to enjoy vacations every year, support families, own nice houses in nice neighborhoods, and thrive in successful careers? Is this because I spent the last 20 years goofing off and watching movies, reading books, playing games? Will I ever catch up? Every time I go online, I see what’s happening in other people’s lives and agonize over it; comparison is the thief of joy, I hear. And I am smart enough to know that social media is an evil rotten thing that makes everyone feel like this, but not in control of my own anxiety enough to always remember that. (The real mundane answer, I think, is that I took a low-paying career despite tens of thousands of dollars in debt and virtually no generational support to speak of. When Dad died and left me a $10000 life insurance policy, that was the most money I had ever seen in my life.) The high art/low art distinction is of course bullshit, but it speaks to a very real anxiety: what if what you’re doing will never be good enough? Will your art be perceived as inferior or a failure simply by virtue of where it came from? Will I?

I could talk about Prometheus for ages, but the short of it was discovering that I could look at art like this was a kind of salvation. Failed art is never necessarily failed; what matters is authenticity, that it is a product of the world in more ways than any of us can ever see, for both its creator and its purveyor. In Andrei Rublev Andrei agonizes over the seeming impossibility of painting the Last Judgment in a way that brings hope to the masses, not merely terrifies them. It doesn’t seem like there is any way to successfully communicate sacred ideas in a hopelessly profane world. Andrei later meets a “holy fool,” a woman who enters the church lost, ignorant, childlike, jumping at shadows, and his encounter with her gives him the inspiration for how to ultimately articulate his masterpiece. The film ultimately argues that Rublev’s vision, the power of his art, does not exist, is simply not possible, without the life he had lived. Labyrinth of Cinema doesn’t happen without Obayashi being on his deathbed. Hiroshima Mon Amour does not happen if Alain Resnais had not already made an anti-war documentary and believing he had already accomplished everything he could with that medium. Gojira doesn’t happen if the Japanese people had not experienced the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Prometheus doesn’t happen without decades of science fiction film giving birth to it. An essay like this doesn’t exist without my lost twenty years, and whatever I do in the future will be a consequence of them alongside a lifetime of feeling out of sync. I don’t get here without Final Fantasy, without A Wizard of Earthsea, without Ezra Pound, without Godzilla Mothra King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack, without Calvin and Hobbes. To change any one thing would warp me into something unrecognizable, something worse.

“I suddenly realized that even if I was given a second chance I wouldn't need it, I really wouldn't.”

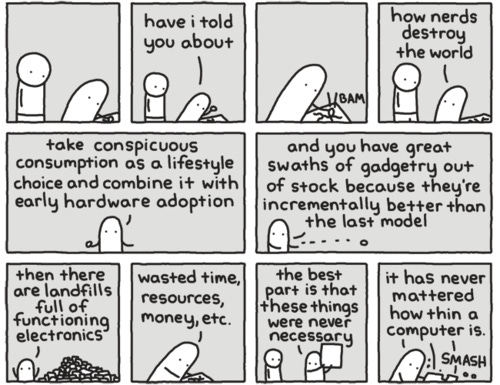

I think it is important to point out that Ezra Pound was extremely wrong-headed about a lot of things, and his attitudes about art and quality drove him down the path of becoming a contemptible fascist. He carried water for Mussolini and Fascist Italy, who had weaponized art, artists, and an idealized past to commit atrocities. This bit here is really the impetus for writing any of this down. I’m extremely worried about the state of media literacy and our relationship with art, post-NFT, post-AI hype. There is a quote you can find easily online from animation auteur Hayao Miyazaki, who is responsible for masterworks like Princess Mononoke (1997) and The Wind Rises (2013), the latter concerning itself exactly with the fear of your love, your art, your pure and innocent desire to create, warped into a monstrosity used for unspeakable horrors. Miyazaki is watching a demo of an A.I. generated animation. It’s rudimentary and ugly. His response is “I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.” Right now, I am both alarmed over the possibility that this essay will eventually get scraped and incorporated into ChatGPT against my will, but also amused by the possibility that some poor high school student will ask it to write a book report about Great Expectations and somehow come away with some factoids about Yukihiro Takahashi and Yellow Magic Orchestra. But when I think about these new high-tech ways of making and stealing art, I’m forced to also remember the webcomic Pictures for Sad Children; in one installment, the nameless main character speaks to the reader:

“have I told you about / how nerds destroy the world / take conspicuous consumption as a lifestyle choice and combine it with early hardware adoption / and you have great swaths of gadgetry out of stock because they’re incrementally better than the last model / then there are landfills full of functioning electronics / wasted time, resources, money, etc. / the best part is that these things were never necessary / it has never mattered how thin a computer is”

The creator of Pictures for Sad Children, Simone Veil, abandoned their work in 2012. They couldn’t fill a pre-order for a published book to the demands and expectations of their audience, and so burned the copies waiting to be shipped and posted a long manifesto about the poisonous relationship between consumers, the consumption of art, and artists. It is all long gone and to the best of my knowledge Veil has never returned to an online presence (so I am speaking from raw, incomplete, imperfect memory), and while Veil was clearly in a bad place and struggling with their emotional and mental needs, the manifesto spoke genuine truths to me, like how VALIS by Philip K Dick spoke scarily rational truths to me despite coming from a place of extreme schizophrenia. Sometimes an idea can get lodged deep into your brain and fuck you up forever. There was a lot of hay over the past year about how NFTs like the Bored Ape Yacht Club were gross and ugly because they were aesthetically unpleasant. While they are, this isn’t why they’re gross. They are gross because they are financial assets. They were designed to be returns on investment: commodities masquerading as art, creative expression the way a mutual fund’s portfolio allocation is a creative expression. (If I were including theory I would make some gesture toward Horkheimer and Adorno here.) To quote Gertrude Stein, there’s no there, there. I feel that A.I. generated art from tools like Midjourney and ChatGPT are similarly insults to authentic expression. They wipe away the lives, the stories, the web of things and moments and histories that go into any singular expression and splice them with a million other works similarly erased of their context and meaning, for the sake of frictionless consumption. Worst of all, they decimate the opportunities of people not already born into wealth and privilege to become artists. Here comes that status anxiety again. Artists have to be allowed to fail.

And I question the ethics and dereliction of responsibility inherent in these new high-tech endeavors. Pound’s feared “tawdry cheapness” paired with his anger over an unfair and exploitative world economy, pushed him into fascism and disgusting antisemitism. His favorite refrain was “make it new!” TS Eliot, a peer and benefactor of Pound’s clout, eventually gave up on democratic ideals and pledged loyalty to the British monarchy. And it’s also important to note that both lived through both World Wars – they justifiably thought the world was going to end. What happens to a world that is increasingly alienated from their own expression? From their own past? From their own present? In Andrei Rublev, Theophanes the Greek says, “What is praised today is abused tomorrow. They will forget you, me, everything. All is vanity and ashes. Worse things have been forgotten. Humanity has already committed every stupidity and baseness, and now it only repeats them. Everything is an eternal circle and it repeats and repeated itself. If Jesus returned to earth, they would crucify him again.” In Hiroshima Mon Amour, the woman says, “Listen to me. I know this, too. It will happen again. 200,000 dead, 80,000 wounded in nine seconds. Those are official figures. It will happen again. It will be 10,000 degrees on the earth. ‘Ten thousand suns,’ they will say. The asphalt will burn. A deep chaos will prevail. A whole city will be raised and once more crumble into ashes.” Movies are a kind of cutting-edge time machine. This last week I watched Oppenheimer (2023), which is an adaptation of the book American Prometheus, and it’s about a man who believes he’s become a monster because he created the atomic bomb with the noble intent to destroy fascists, but who also knows it will likely destroy everything along with them. Labyrinth of Cinema doesn’t exist without it.

Why is the world so different from what we thought it was?

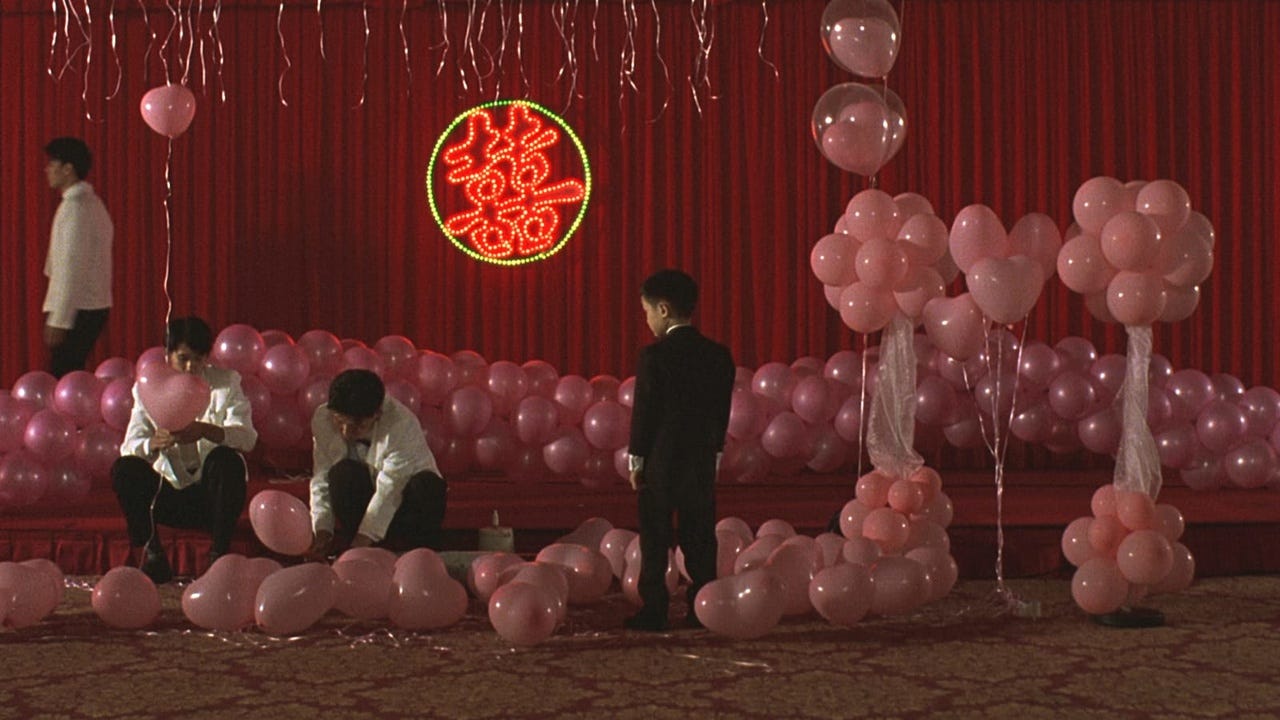

My favorite movie I watched for the first time this year is Yi Yi (2000) from Edward Yang. The English, international subtitle is “a one and a two,” and the title translates literally to “One one.” It’s about a family in Taiwan, living their lives together but also in isolation. The father, NJ, has a chance encounter with his first love Sherry, not seen in decades. The mother, Min-Min, her mother is dying, and coming face-to-face with mortality flings her into an emotional crisis, frustrated and grieving for how her life has turned out and how small and dull it is. The daughter, Ting-Ting, is coming of age, entering her first romantic experiences, facing guilt that her grandmother collapsed doing a chore intended for her. Her only reference point is romantic movies: “Why is the world so different from what we thought it was?” she asks her comatose grandmother at one point, trying to figure out why her love interest, Fatty, is so mercurial.

The son, preschooler Yang-Yang, has questions nobody can answer, curious about the world and frustrated by his limited perspective; “I can only see what's in front, not what's behind. So I can only know half of the truth,” he says to his father NJ. He starts taking photographs of the backs of people’s heads to help them out. But NJ does not leave his life and family to pursue what could have been with Sherry. Instead, he comes home and finds his wife, her mother now passed, and her crisis healed to some degree by a health retreat. Fatty says to Ting-Ting on their first date, “my uncle says we live three times as long since man invented movies…it means movies give us twice as much from daily life.”

Image Sources:

Images for Labyrinth of Cinema from https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/labyrinth-of-cinema-movie-review-2021

(Produced by Crescendo House, 2019)Images for Andrei Rublev from https://www.janusfilms.com/films/1827

(Produced by Mosfilm, 1966)Images for 2001: A Space Odyssey from https://screenmusings.org/movie/blu-ray/2001-A-Space-Odyssey/pages/2001-A-Space-Odyssey-0001.htm

(Produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1968)

Images for Prometheus from https://www.cap-that.com/prometheus/index.php?image=prometheus(2012)_cap0001.jpg

(Produced by 20th Century Fox, 2012)Images for Yi Yi from https://mubi.com/de/us/films/yi-yi-a-one-and-a-two

(Produced by Kuzui Enterprises, 2000)Calvin and Hobbes from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Comics-High-or-low-art-CALVIN-AND-HOBBES-C-1993-Watterson-Reprinted-with-permission-of_fig4_326395975

Pictures for Sad Children from https://paullicino.tumblr.com/post/78123427880/on-pictures-for-sad-children